Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

By A/Prof Leo Donnan

- Home

- Patient News

- Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a spectrum disorder that affects the neonatal and infant hip. It is used to describe the condition in which the femoral head has an abnormal relationship to the acetabulum. Developmental dysplasia of the hip includes complete dislocation, partial dislocation or instability wherein the femoral head comes in and out of the socket. The term also includes an array of radiographic abnormalities that reflect inadequate formation of the acetabulum. Because many of these findings may not be present at birth, the term developmental more accurately reflects the biologic features than does the term congenital.

In 2003-2004, DDH was the fourth most common birth defect in Victoria, with a prevalence rate of 29.6 per 10,000 births (Riley and Halliday 2006). Since 1993, there has been no significant change in the prevalence rate.

Early detection of DDH is vital, as if left untreated, can lead to chronic pain, gait abnormalities and degenerative arthritis. By contrast, early conservative management allows the hip joint to develop normally, minimising the need for surgical intervention and reducing the risk of long term disability.

Clinical screening programs appear to reduce the number of late invasive interventions performed but depend on the training and expertise of the examiner. In the neonatal period, screening for DDH is performed as part of the routine examination of the newborn. Screening is continued after discharge from hospital as part of the regular maternal child health care assessments from hospital to detect those children who are missed or develop the condition at a later stage.

However, it should be noted that more than 60% of infants with DDH have no identifiable risk factors.

Aetiology and Incidence

The aetiology of DDH is multifactorial, involving both genetic and intrauterine factors.

Capsular laxity, from what ever cause, is the most common underlying pathology in the development of hip dysplasia. Capsular laxity results in excessive movement of the head within the hip socket, which can lead to distortion of the acetabulum and dislocation

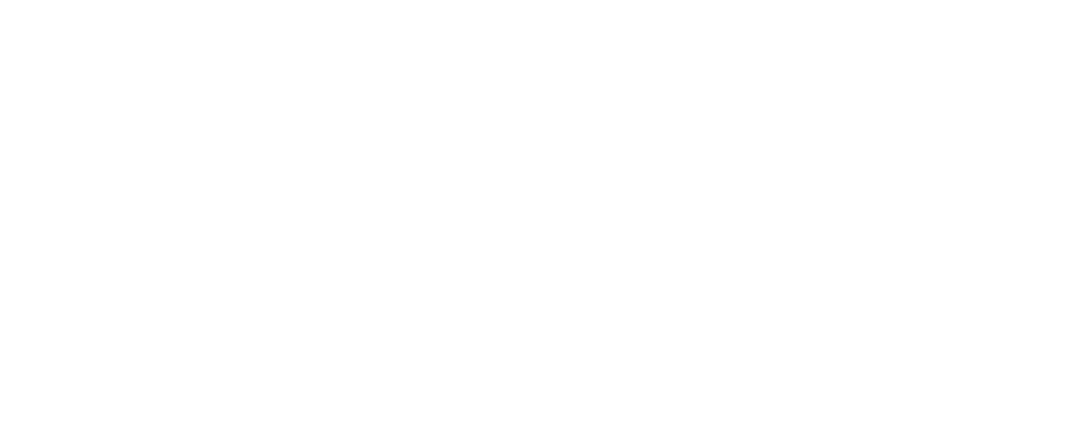

Understanding the secondary changes in the hip joint helps with interpreting clinical signs. Dysplasia results in morphological changes to the shape of the femoral head. Loss of a spherical socket means that the head is no longer moulded and it takes on a progressively more ovoid or egg shape. If the femoral head moves out of the socket, the adductors and psoas muscles become tight due to their natural line of pull being disturbed. Initially these changes may only be mild and can be corrected by positioning the hip in an abducted and flexed position. With time, the changes become progressively fixed and it may not be possible to reduce or hold the hip in a satisfactory position within the joint.

The reported incidence of DDH depends upon the definition of the pathology, the screening methodology (clinical, sonograhpic, or radiographic), and the population reviewed. Dislocation of the hip has been reported in the literature to have an incidence of approximately 1 in 1000 live births with the rate varying between ethnic groups. Instability occurs in approximately 1 in 100 live births.

In 65% of cases, hip dysplasia affects the left hip. Bilateral dysplasia occurs in 20% of cases so the examiner needs to be aware that bilateral hip dislocations, especially if fixed, may appear normal with symmetrical signs. These types of hips are often only identified late.

Risk factors

- Female sex account for nearly 80% of cases of DDH - it is thought that the affect of maternal hormones on the foetus predisposes females to ligamentous laxity.

- Family History of DDH - although not following a recognised genetic inheritance pattern, the incidence of DDH increases if a first degree relative has been affected

- Breech presentation - results in extreme flexion and limitation of hip motion causing capsular stretching and acetabular dysplasia.

- Intrauterine packaging problems - a relative reduction in uterine volume may result in a number of so called “packaging disorders” during which DDH may occur. e.g plagiocephaly, congenital muscular torticollis, foot deformities (metatarsus adductus, calcaneovalgus)

- Wrapping or swaddling - there is clear evidence that the practice of comfort wrapping that included the infants legs is extremely detrimental to the hips development and directly associated with the development of dysplasia and dislocation

However, it should be noted that more than 60% of infants with DDH have no identifiable risk factors.

Physical Examination

A successful examination for DDH requires a warm and quite environment with the infant relaxed, well fed and lying on an insulated firm surface. The infant should be unclothed from the waist down.

General Examination

The general examination of the infant may raise the possibility of associated hip dysplasia. Most signs relate to packaging issues but occasionally a more serious feature is identified of which hip dysplasia is but one of the associated anomalies.

Order of Examination

It is recommend testing for hip instability first and then asymmetry, followed by the general inspection. It is important not to test for hip adductor tightness before testing hip stability, as the manoeuvre of stretching out of the flexed hips may cause discomfort. This will reduce the likelihood of the infant becoming unsettled, either from exposure or handling.

Instability

The Barlow and Ortolani tests are used to assess for hip instability. Each hip should be examined separately. These tests have a high specificity (100%) but a low sensitivity (66%) However, the sensitivity of the tests can be improved if undertaken by an experienced examiner.

Barlow Test

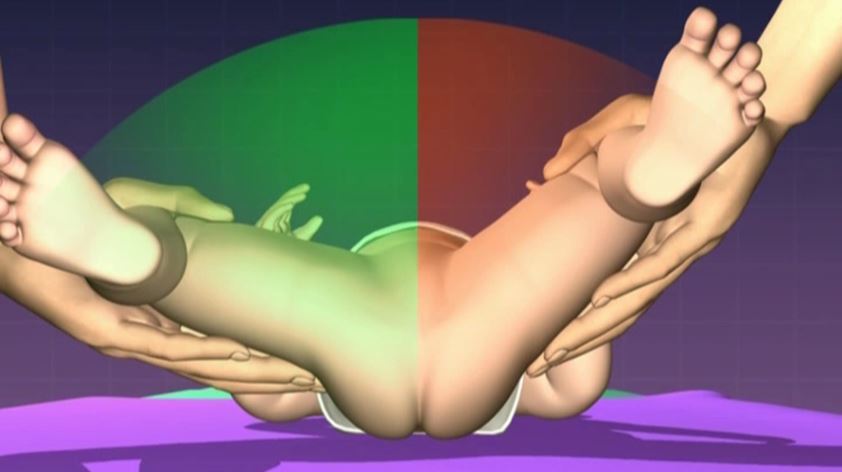

The Barlow test is a provocative manoeuvre used to uncover hip instability. The test is performed by standing at the end of the examination couch facing the baby. One hand stabilises the pelvis whilst the other grasps the knee and flexes the hip to 90 °. The examiner’s fingers should lie over the greater trochanter with the thumb resting on the inner side of the thigh. The hip being examined is then adducted by 10-20 °. Gentle, but firm, backward pressure is then applied.

A small amount of movement is usually detectable in the neonatal hip, which disappears after a few weeks. If instability is present, a gliding sensation will be felt, due to the femoral head riding up onto the edge of the acetabulum. This indicates that the hip is subluxating. If the hip is dislocating, the gliding sensation is present but is followed by a distinct loss of resistance as the femoral head escapes the socket.

Ortolani Test

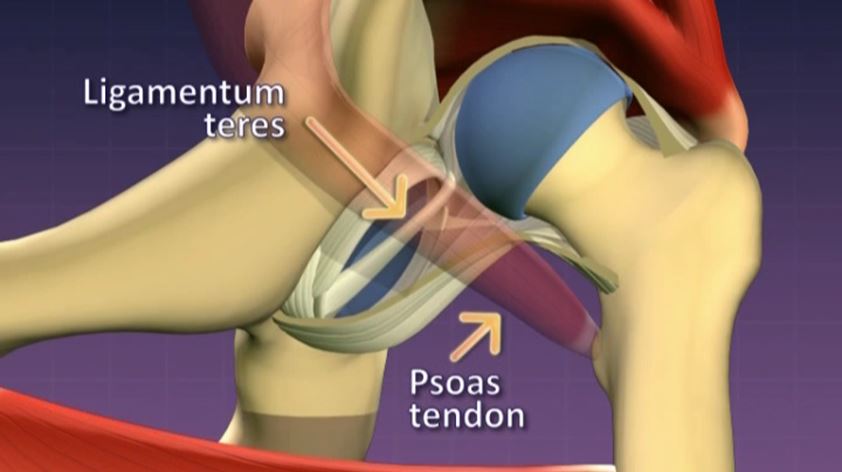

The Ortolani test is used to reduce a dislocated hip. The examiner stands at the end of the examination couch. Both hips are flexed to 90 °, with the knee grasped and thigh held between the thumb and index fingers. The second and third fingers lie over the greater trochanter and as the hip is gently abducted, these digits attempt to lift the dislocated femoral head into the acetabulum reduces. If the leg is then allowed to adduct the hip dislocates and the leg appears to shorten.

Asymmetry – Limitation of Abduction

The Barlow and Ortolani tests become less sensitive in the older infant due to the development of soft tissue contractures and the larger body size. The most sensitive sign of hip dysplasia in the older infant (over three months) is a reduction in hip abduction.

With the examiner standing at the end of the examination couch, both hips are flexed to 90 °. The hips are then abducted slowly, allowing the hips to gently stretch out. Asymmetry is detected by comparing the range of hip motion and assessing the degree of resistance between the two sides. This manoeuvre must be performed gradually as many infants will find it uncomfortable, particularly if hip dysplasia is present. It may be best to repeat this test a couple of times, increasing the abduction each time to allow the infant to become comfortable with the examination. If this test is done well even minor degrees of dysplasia can be detected.

Other features that may arouse suspicion of DDH include shortening of the limb (Galeazzi sign) and asymmetrical thigh or gluteal creases. It is important to note that asymmetrical creases are common at all ages, especially in neonates. They are a soft sign of hip dysplasia and by themselves are not diagnostic.

Clicks

Audible “clicks” or “snaps” are common during the examination of the hip. Such high pitched “clicks” are thought to be due to ligament movement and are not to be confused with the low pitched, palpable “clunk” of the reduction of the dislocated hip. If all other signs are normal, these soft tissue clicks are usually innocent but if doubt exists in the examiners mind, further investigation may be warranted.

Imaging

Ultrasound

Before the age of six months the infant’s hip is largely cartilaginous, therefore ultrasound is the investigation of choice. As there is no exposure to radiation, repeated evaluation is safe.

In the presence of a normal examination, imaging should be considered for an infant with breech presentation, family history or other risk factors such as the presence of packaging disorders.

Paediatric ultrasound is a specialised investigation that should only be performed by medical imaging departments that perform this examination routinely.

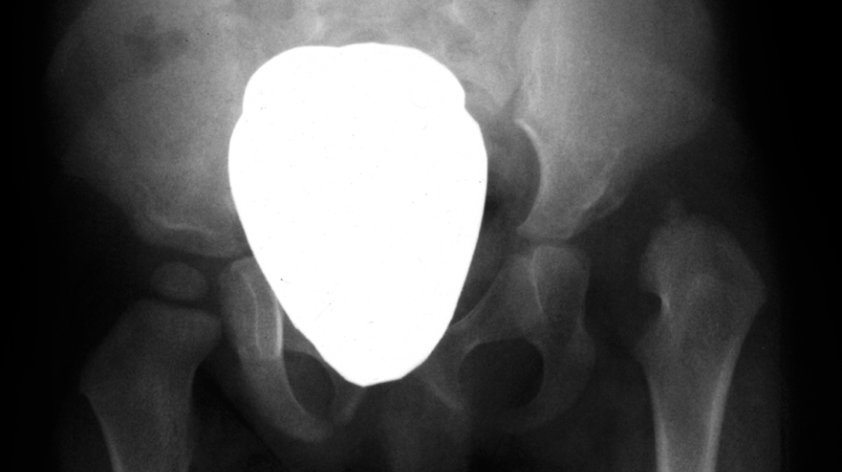

Radiograph

After the age of six months the plain radiograph is a more useful investigation than ultrasound as the bony development is advanced enough to allow a complete assessment of the hip.

It is recommended that for children under the age of two, that the service performing the imaging has expertise in paediatric radiology.

Screening

In Australia, screening for DDH is performed as part of the routine examination of the newborn. Serial clinical examination is continued after discharge from hospital and is performed by a number of health professionals including GPs, maternal and child health nurses and paediatricians.

Although the efficacy of screening for DDH is still a topic for debate, there is evidence to suggest that clinical screening, when undertaken by experienced and trained staff is effective.

The role of routine ultrasound examination of the neonatal hip remains controversial due to issues of over sensitivity, potential for over treatment and cost.

Currently, there is no formal process by which health professionals are credentialed in the technique of the examination of the infant hip.

Indications For Referral To A Paediatric Orthopaedic Surgeon

Referral to a paediatric orthopedic surgeon is indicated when the

- there are significant risk factors present

- clinical examination is abnormal

- medical imaging examination is abnormal

Hip Dysplasia Clinic At St Vincent's Private East Melbourne

In a single site we aim to provide families with suspected or established hip dysplasia high quality supervised hip ultrasonography, brace fitting and adjustment, physiotherapy screening and education all supervised by Assoc Prof Leo Donnan and Mr Brian Loh

This is integrated care model is closely linked to the International Hip Dysplasia Institute to ensure patients and families receive the best information and care and the opportunity to be part of the International Hip Dysplasia Registry.

References

1. Pediatrics AAo. Clinical practice guideline: early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2000 Apr. Report No.: 0031-4005 (Print).

2. Chan A, McCaul KA, Cundy PJ, Haan EA, Byron-Scott R. Perinatal risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1997 Mar;76(2):F94-100

3. Salter RB. Etiology, pathogenesis and possible prevention of congenital dislocation of the hip. Canadian Medical Association journal 1968 May 18;98(20):933-45.4. Martus JE, Sucato DJ. Developmental dysplasia of the hip age 0 – 8 years. Current opinion in Orthopaedics 2007;18:529-35.

5. Guille JT, Pizzutillo PD, MacEwen GD. Development dysplasia of the hip from birth to six months. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2000 Jul-Aug;8(4):232-42.

6. Cady RB. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: definition, recognition, and prevention of late sequelae. Pediatr Ann 2006 Feb;35(2):92-101.

7. Eastwood DM. Neonatal hip screening. Lancet 2003 Feb 15;361(9357):595-7.

8. Leck I. An epidemiological assessment of neonatal screening for dislocation of the hip. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London 1986 Jan;20(1):56-62.

9. Myers J, Hadlow S, Lynskey T. The effectiveness of a programme for neonatal hip screening over a period of 40 years: a follow-up of the New Plymouth experience. The Journal of bone and joint surgery 2009 Feb;91(2):245- 8.

10. Barlow TG. Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Congenital Dislocation of the Hip. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 1963 Sep;56:804-6.

11. Kamath S, Bramley D. Is 'clicky hip' a risk factor in developmental dysplasia of the hip? Scott Med J 2005 May;50(2):56-8.

12. Kane TP, Harvey JR, Richards RH, Burby NG, Clarke NM. Radiological outcome of innocent infant hip clicks. Journal of pediatric orthopaedics 2003 Jul;12(4):259-63.

13. Schwend RM, Schoenecker P, Richards BS, Flynn JM, Vitale M. Screening the newborn for developmental dysplasia of the hip: now what do we do? Journal of pediatric orthopedics 2007 Sep;27(6):607-10.

14. Macpherson KawnonfHSp. Screening hips of newborns in Scotland: a Health Technology Assessment scoping report. In: QIS) NQISN, editor, 2009.

15. Ortolani M. [Clinical diagnosis made by examination of the rebound phenomenon is the only method permitting truly early & total treatment of congenital hip dislocation.]. Bulletin de l'Academie nationale de medecine 1957 Mar 5-12;141(9-10):188-93.

16. Dezateux C, Rosendahl K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Lancet 2007 May 5;369(9572):1541-52.

17. Patel H. Preventive health care, 2001 update: screening and management

Definitions

- Instability - a hip that can be provoked by manipulation to either subluxate or dislocate from a reduced position

- Subluxation - where the femoral head has partial contact with the acetabulum

- Dislocation - where the femoral head has complete loss of contact with the acetabulum.